9 Now-Defunct Grocery Chains You Probably Forgot Ever Existed

In the heady economic days we're currently living in, groceries come more and more from big box stores and online conglomerates than old-fashioned supermarkets like those we were wheeled through by parents and grandparents on shopping days. While some of the old chains still exist, most owe their continued existence to being part of a giant conglomerate themselves, and with all the tricky dealings that come with that.

The familiar markets that employed our children, neighbors, and friends are quickly becoming a thing of the past, tumbling toward the same obsolescence as the milkman and the ice delivery truck. In fact, some of the best-known and most well-loved names in the supermarket business have already gone the way of the dodo, providing cautionary tales to those that remain. There are still some markets that can provide that old-school feeling and other unique grocers that deserve to be cherished, but let's take a trip down memory lane and see which ones are a thing of the past.

1. Waldbaum's

When Izzy Waldbaum opened a small dairy shop in 1904, he started a business that would, by the end of the 20th century, become a ubiquitous New York fixture. While his first foray into the grocery business was located in Brooklyn, more than 130 would open by 1985, stretching from a high concentration on Long Island and NY's outer boroughs across the Northeast.

The first of these to be branded as a "supermarket" opened in 1950 in Flushing, Queens, three years after Izzy Waldbaum's death. But by then, the store's founder had created a corporate structure and values system that not only saw his stores proliferate across the suburbs but also acted as an agent of change. In 1938, Waldbaum had hired two black checkout clerks, a first in what was still a quietly segregated city; both would eventually move up the corporate ladder to become executives.

The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company (better known as A&P, another entry on this list) bought Waldbaum's from the family in 1986 for $287 million or $50 per share. At the time, Waldbaum's was the nation's 12th-largest supermarket chain, and it would remain in business until A&P itself went under in 2015.

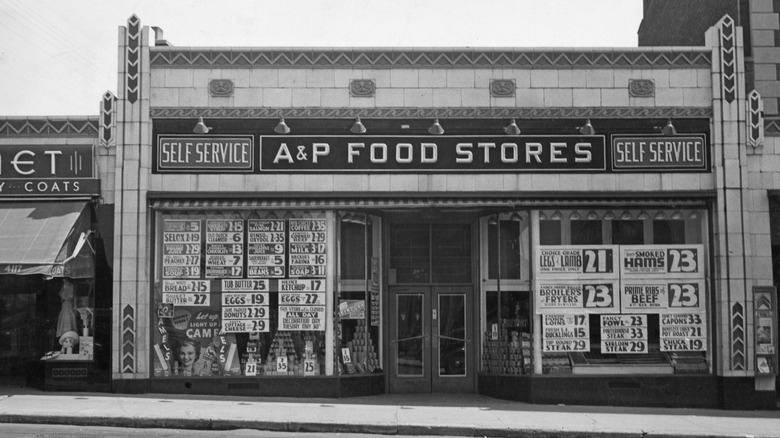

2. A&P

31 Vesey Street in Manhattan sits in the middle of one of the most bustling urban areas in the country, and has, since the 1800s, seen the expansion of New York upward from the southern tip of the island. It was into this growing hub of humanity that George Huntington Hartford and George Gilman entered the mail-order tea business in 1859. They originally called their store, quite patriotically, the Great American Tea Company, but by 1870, it had been renamed to The Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company (A&P for short).

Over the next several decades, A&P built a reputation as fair dealers in quality and price, to the point that in 1912, the company opened its first "economy store." Usually located away from the main streets, operating on short-term leases that allowed them to go where the rent was cheapest, these stores were the precursor to the modern supermarket. These were places where folks could get all of their dry goods and produce in a single place at a reasonable and clearly stated price.

By 1939, the word "supermarket" had entered our lexicon, and A&P owned no less than 1,100 of them. However, as the supermarket business grew and changed, A&P saw itself sold to a succession of outside owners, continually declining from its peak as one of the top chains in the country. At its peak, A&P had more than 15,000 stores, but by 2006 that number had dwindled to less than 400, and in 2015 the chain closed for good.

3. Alpha Beta

During the years between 1917 and 1995, Alpha Beta was more than just a supermarket; it was also the name of the organizational principle that dictated the success of the entire supermarket model. An inside term for the alphabetical layout of products in supermarkets, Alpha Beta would soon become a byword for easy shopping for generations of customers. Albert and Hugh Gerrard first organized their Triangle Grocerteria this way in 1915, and two years later opened the first Alpha Beta market in Pomona, California.

The Gerrards' original business was bought by American Stores in 1961, and later by Skaggs Drug Centers in 1979. This acquisition caused a huge change in the beloved Alpha Beta store model, combining food and drug stores in Alpha Beta's territory and rebranding as Skaggs Alpha Beta. After Skaggs' ownership, most of the Alpha Beta stores throughout the west were rebranded and eventually subsumed by Lucky, which soon changed its own name to Albertson's. In this mess of name changes and ownership moves, the last Alpha Beta markets were doomed.

4. Kash & Karry

In 2007, a Florida supermarket staple said goodbye after more than 50 years of business as the final Kash & Karry was converted to a Sweetbay. "Kash n' Karry at one time was a strong brand and served as a pillar for the Tampa Bay community," Shelley Broader, president and chief executive officer of Sweetbay Supermarket, announced in a prepared statement. "We wanted to treat Kash n' Karry with respect and retire the company gracefully, and I am very proud that we have."

The chain used the name Kash & Karry starting in 1962, but the chain's origins go all the way back to 1914, when Italian immigrant Salvatore Greco began selling fruits and vegetables in the streets of Tampa from the back of a pre-owned horse and wagon. By the mid-1970s, K&K's Tampa distribution centers were overseeing stores in 11 countries. Purchased by a conglomerate group in 2001, K&K was looking down the barrel at a similar fate to the other markets we've featured. It was soon folded into a new supermarket concept, Sweetbay, which would itself eventually rebrand many of its stores to Publix.

5. Bruno's

An Alabama staple, Bruno's was founded in Birmingham by Joseph Bruno, the son of immigrants from Sicily, in the economic nightmare years of the Great Depression. Using his family's $600 in savings, Bruno opened a small grocery store in the heart of the city. According to the Joseph Bruno Charitable Foundation, Bruno's Grocery Store, on the corner of Eighth Avenue North and Tenth Street in Birmingham, would have fit inside a modern meat cooler. But from these humble beginnings, Bruno would create a powerhouse of Southern business.

Both Piggly Wiggly and Food Fair were part of the original Bruno empire, making what started with a single store into a billion-dollar business. It was so successful, in fact, that in 1995, Bruno's was sold to Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Company, a New York investment concern with holdings in other supermarket companies, for $1.3 billion, completing the Bruno family's ascent from Sicily to an outsized slice of the American Dream.

6. Pathmark

A former staple in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, Pathmark began in 1947 when independent New Jersey grocers felt the need to organize in order to compete with the ever-growing number of conglomerate supermarkets. Among the members of this cooperative was a subgroup called Supermarkets Operating Co., formed in 1956 by Alex Aidekman, Herb Brody, and Milt Perlmutter. At their peak in the late 1990s, Pathmark, the main hometown brand owned by the cooperative, had more than 140 stores operating. But before long, Pathmark was the only remaining brand in their portfolio, and a takeover by A&P (which is becoming the unintended star of this article) loomed.

After the takeover in 2007, Pathmark's decline began. UFCW Local 1500, which represented Pathmark's workers, wrote before the final store shut down in 2015, "As you went to work every day [during the A&P era, you were forced to sit back and watch as the ever-changing cast of A&P executives ran these once profitable stores into the ground." When A&P went out of business in 2015, Pathmark went with it.

7. Penn Fruit

Samuel Cooke isn't the only rags-to-riches founder featured in this piece, but he may have been the most natural entrepreneur. After completing a grammar school education in only six years before dropping out and selling vegetables door to door from a basket, Cooke moved up to a pushcart, a storefront, and eventually an empire. Though he owned more than 50 stores in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York, Cooke's biggest business idea was far superior. Conceived with Piggly Wiggly founder Clarence Saunders, self-service kiosks were introduced in the 1920s.

As a result, business soared. In the 1950s, per-store sales at Cooke's Penn Fruit were over three times the national average. But it seems that without Cooke's guidance, the stores had an expiration date. A decade after Cooke's death in 1965, Penn Fruit filed for bankruptcy, changed its name to "Dale's", and ceased all operations by 1979.

8. Bells

A Western New York staple for four decades, Bells markets were the epitome of old-fashioned meat and potatoes grocery shopping, which made the 2009 closure of the last location an especially hard pill to swallow for Buffalo and Rochester area shoppers. The fact that the beloved storefront was being replaced with a Whole Foods must have seemed like a harbinger of a new paradigm. Folks didn't want the simple fare offered by older markets like Bells; shoppers wanted organic, local produce and modern conveniences.

In the Noe Valley Voice, customer Mercedes Marenco, 88, lamented losing Bells within her local community. Having been a resident for over five decades, she would miss the familiarity and camaraderie of this staple, as well as being able to purchase 10 pounds of pears for $1.

As to how Bells declined in the first place, that story is sadly familiar: A series of mergers left Bells in the hands of non-local chains, first Ralphs Supermarket, then Kroger. Soon, like so many other once-proud brands relegated to portfolio filler, Bells was living on borrowed time.

9. 365 Market By Whole Foods

When Whole Foods was founded in the 1980s, it represented the dream of Reagan-era former hippies perfectly: a high-end capitalist beacon that would bring organic and health foods to the masses. It would connect small farms to local markets in yuppie areas and bring the organic movement mainstream. Having successfully done so over the following three decades, Whole Foods again innovated in 2016, offering a more affordable chain of markets known as 365.

However, just three years later, Whole Foods stopped the growth of these standalone locations as prices continued to change. After being acquired by mega-corporation Amazon, Whole Foods' new higher-ups cited a closing price gap between the flagship stores and the 365 Markets as inflation began its relentless march into the 2020s. In a statement, Whole Foods CEO John Mackey made the death of 365 official, saying, "We have decided that it's in the best long-term interest of the company to concentrate our efforts on growing the core Whole Foods Market brand moving forward."