How Public School Lunches Have Evolved Over The Years

Nothing brings back the nostalgia of the school lunchroom quite like angst over the social pecking order and rectangle-shaped pizza. Cafeteria ladies and gents have been dishing out hot lunches, to-go breakfasts, and ala carte snacks for decades. But school lunches didn't always look the way that they do today. Even now, meals served in U.S. school cafeterias are very different than those served in other countries.

The public school lunch program officially began in the 1970s. But lunch was served decades before as teachers realized that hungry students had trouble learning and that childhood hunger was a big problem. Packed sandwiches and other quick meals from home were an option for some students, but many didn't have access to nutritious food or were unable to bring what they needed the long distance to school. So provided meals became more of a priority.

The earlier versions of school lunches were provided by local groups and individuals, but as the education program in the United States developed, so did the attention to what students ate. Here are the types of food that students could expect to find in the cafeteria, from hot items packed at home to pizza and nuggets.

European models in the 18th century

It was actually an American-born physicist and statesman, Count Rumford, who moved to Germany and started public lunch for school-aged children in the 1790s. He provided lunch and education in reading, writing, and arithmetic to impoverished children. They had to work part-time as well, alongside poor adults, making clothing for the Army. Both the kids and. the adults were given food as part of the work and study program.

A typical meal included potato soup with barley and peas because it was cheap and could be made in bulk. Students didn't get to enjoy elevated flavors or extras like vegetables and meat. The focus was not on balanced nutrition as we understand it today, but rather on providing sustenance on a budget. There wasn't a lot of funding for Rumford's program, so he had to get creative and look for food that had a lot of bang for the buck.

This model influenced many other countries in the following years. Rumford worked with England, Germany, Scotland, France, and Switzerland to develop similar programs that provided food assistance on a large scale. These early European public lunches eventually came to the U.S. in schools as well.

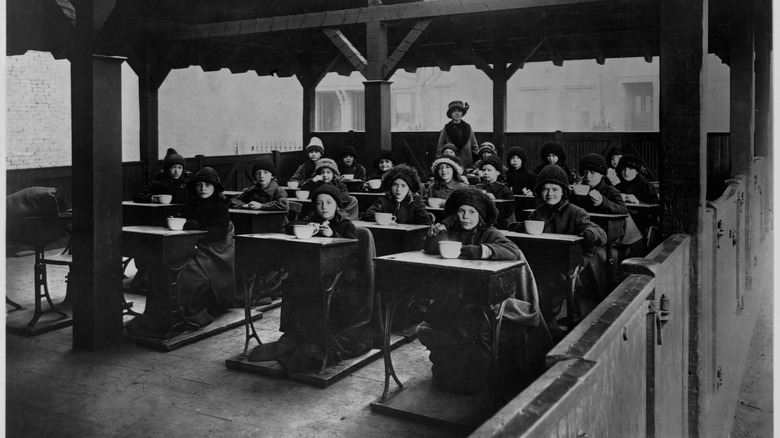

Children's Aid Society of New York in the 19th century

Early school lunch programs in the U.S. relied on private organizations, and those interested in caring for impoverished children, to assist with food. Many programs began out of a need and focused mostly on local schools.

The Children's Aid Society of New York started providing free meals in 1853 at the industrial school. To increase attendance, the school included a free meal at noon each day for pupils. With little funds, however, it wasn't very nutritious. This did bring more attention to the need for good food for school-aged children, which helped lay the groundwork for future initiatives.

The first school lunch program to be self-sustaining was in Boston around 1894. Ellen Richards took over the previous school lunch duties and brought in trained personnel and a focus on nutrition. Students paid for school lunches, which helped fund higher-quality food as well. A typical meal had peanut butter sandwiches or pea soup, plus a small half-pint of milk. Including milk instead of water in school lunches started around this time because it was filling and had added nutrients. Keeping milk on the menu continued and even increased over the years.

Early 1900s lunches included soup and rolls

As the school lunch program expanded, those in charge still had to deal with small budgets. They recognized the need for nutritious food that provided what children needed to grow and thrive, so soups were used to get protein, carbohydrates, and fats into the diet. These dishes were still pretty simple and often didn't have a lot of meat or vegetables. They relied on what was available locally, either grown or donated by the community.

In Milwaukee, soup and rolls were prepared by volunteers who lived near the schools. They were sold for 1 cent or free for children unable to pay. In some areas, home economics classes also made lunches for students at the school occasionally. William Penn High School in Philadelphia taught its all-female student body how to can and preserve food as part of a cookery class. This food was later used as part of the school lunch program, which helped keep it self-sufficient. William Penn High School was also one of the first to transfer the responsibility for school lunches to the school board rather than charitable donors and private organizations.

In the 1910s, lunch quality varied widely

There wasn't a lot of consistency, even when the lunch programs became commonplace. Concessionaires prepared and provided the food, but it could be hard to budget because they were never sure what kind of income they could expect. Many private charitable organizations and groups stepped in, especially as the public became more aware of childhood hunger as a social problem.

Common items around this time included milk, vegetable soup, and hot lunches. Many elementary-aged children went home for lunch, however, this wasn't always possible, especially for families with two working parents. In some areas, school lunches included younger pupils while in others, only older students stayed for lunch. What was offered largely depended on what was needed rather than a universal policy.

One interesting aspect of the school lunches at this time was that they were tailored to individual student populations. Those in charge didn't want food to go to waste, so they had to make sure that they were sensitive to cultural differences, especially since this was also a booming time for immigration. Areas with a large Italian-American population often served pasta and Italian bread, while areas with Irish immigrants included hearty stews and sliced bread in their menus.

The Great Depression brought in state and federal funding for lunches in the 1920s and 1930s

Malnourishment became more of an issue as more families faced poverty during the Great Depression. People had to get creative to make the most of food they had, so dishes like Hoover stew and water pie became staples on the table.

During this time, many states began to fund school lunch programs, and later, the Works Progress Administration helped bring hot lunches that included meat. This program provided employment opportunities for adults, which helped families, while also making sure that students were fed and ready to learn. Farmers unable to sell their wares since many people were struggling to get enough money to buy food. The government stepped in, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture bought food, providing income to farmers, which they used to feed the public.

Even though many of the programs had more oversight at this time, it was still a challenge to keep things funded. In addition to tax-payer dollars, organizations and parents donated money and food. This helped offset the costs and ensured all students had access to healthy food that provided nutrients. In many cases, especially in rural areas, the hot lunch a child got at school was the only complete meal they ate all day. The focus was on hot meals, such as soups or stews, plus bread and beans.

School lunch becomes a federal program in the 1940s and 1950s

The National School Lunch Act was signed in 1946. Under federal law, public school lunches now had funding, but had to meet certain requirements. This is when the free and reduced-cost lunch program officially began. Previously, schools relied on generous donors to help cover the costs of meals for students who couldn't afford a hot lunch. The government subsidized the meals to help students who qualified based on their household income. All students eating lunch had the same meals, regardless of whether they paid full price, a reduced cost, or got meals for free.

Schools now had to include milk, protein-rich food like (meat, cheese, peanut butter, or eggs), vegetables or fruits, bread or grains, and butter. The Act outlined specific guidelines, which up to that point had been left up to states and local school boards. Now that there were regulations, schools introduced common staples that were cost-effective and nutritious.

Molded plastic lunch trays also started around this time. This helped students carry their food around the cafeteria easily and kept costs down since the staff could wash and reuse these serving items. The National School Lunch Act began what we recognize today as the modern school lunch program.

School breakfast begins in the '60s

During the '60s, the lunch menus stayed pretty consistent, but the funding for meals saw some major changes that helped it expand. The federal funding for state-run school lunch programs was working, providing nutritious food to hungry kids so that they could effectively learn in the classroom. So in the '60s, the government expanded things further. Further legislation under the Child Nutrition Act of 1966 added a school breakfast option to the cafeterias. Like with lunches, students who were unable to pay fell under the free and reduced-cost option.

Schools first offered breakfast in areas with higher poverty rates or rural districts where students had to travel longer distances to get to school. Things were pretty simple, with items like fruit and toast on the menu. The pilot program was very successful and school breakfast eventually became a permanent fixture in cafeterias in 1972.

The Child Nutrition Act of 1966 also changed the structure of managing school lunches and put it under the USDA. This was meant to streamline things and maintain clearly communicated regulations about nutrition, sanitation requirements, administration, and funding. The Special Milk Program and authorization to fund meals associated with summer school and programs were also added during this time.

Pizza is added in the '70s

Nothing quite screams school lunch like rectangular pizzas. Love it or hate it, this cafeteria pizza dates back to around 1970, when it joined the lunch menu. It was easy to prepare and popular with students. Cafeteria pizza is likely one of the menu items most associated with school lunch thanks to its recognizable shape and distinct texture. The dough was very thick and could be rolled out in large sheets. This made it easy to prepare and cook large portions, which were then cut into individual servings at lunchtime.

The '70s also brought canned options, such as fruit cocktails and vegetables. Desserts often included Jello and similar items that were easier to make in bulk. Some came in individual servings while others were ladled directly onto each student's tray. Condiments were having a heyday during the '70s and appeared on vintage '70s desserts. You can be sure the school-aged children were dousing their food in ketchup as well.

School cafeterias tried to cater to food that kids would like while keeping within the required nutrition guidelines. Tacos, grilled cheese, and spaghetti added to the variety. Meals were often on rotation so that students knew what to expect from day-to-day but weren't served the same thing every lunch. Students have been looking forward to school pizza day for more than 50 years!

Lunch in the '80s and '90s

There weren't a lot of sweeping changes to school menus in the '80s and '90s, but cafeterias remained some of the social hotspots at schools. Lunches included a hot option, sides, and a few a la carte selections. Students stopped going home for lunch and instead could bring a bagged lunch or purchase lunch at school.

Students could expect to see many of the items introduced in the '60s and '70s, meaning school lunches had a sense of nostalgia. Parents saw their own children eating similar meals, including the still-popular rectangle pizzas. Depending on the school's cafeteria layout, students ate at long or circular tables with benches or chairs.

Funding remained an issue and in the early '80s, the federal government tried to lower the funding to states to provide school meals. This led to the portrayal that then-President Ronald Reagan declared ketchup as a vegetable to meet the nutrition requirements. The reality is that the USDA, not the President, needed to find ways to make school lunches more affordable for the government and unfortunately, the items offered were impacted. School lunches got the reputation as bland, cheap, and lacking in real nutritional benefit.

School lunch nutrition overhaul in 2010

Lunches at school didn't see a lot of changes for quite a few years, but eventually, the nutrition of the food came into question. Even though items like Jello and chips were popular with students, they didn't always provide enough protein and vitamins.

It wasn't until decades later that the nutritional profile of school lunches was looked at with much scrutiny. With the passage of the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act in 2010, providing meals that included valuable nutrients while also battling the childhood obesity epidemic in the United States became the focus of school lunches. First Lady Michelle Obama was a big supporter of the changes and did a lot to promote healthy lifestyles for American children, including overhauling school menus.

Increases in veggies and fruits, whole grains, and low-fat milk were added. Overly processed options with a lot of sodium and foods high in added sugar were taken off the menu. Breakfast was still offered, as it gave students a sound nutritional start to the day. By this point, as many as 30 million children ate school-made breakfasts and lunches each day. Some paid for the meals, but the free and reduced-cost program remained for qualifying students to ensure that all had access to nutritious and balanced meals.

Updates throughout the decade included new initiatives to get more local produce in the supply chain, updated equipment, and nutrition education available for staff and students.

Free lunches starting in 2020

The COVID-19 pandemic and the focus on reducing the spread of germs brought some changes to the food industry (such as Texas Roadhouse getting rid of its peanut buckets). But children who had previously relied on school lunches for nutrition were hit pretty hard. As schools went virtual for an extended period during the pandemic in 2020, on-site lunch consumption halted. Fortunately, school districts pivoted to a different model that ensured kids had food to eat even when they weren't in school in person.

In previous years, parents had to provide income information to qualify for free and reduced lunches and breakfasts. With the extra relief funds, schools were directed to provide universal free meals. They still had to adhere to social distancing requirements, but students could pick up free breakfasts and lunches in to-go bags from school sites. Even students who were not enrolled could participate, ensuring that all children were able to maintain healthy nutrition during a time of turmoil.

This went through the 2022-2023 school year when meal programs went back to the previous model where students had to pay unless they qualified for the free and reduced program, which remained. The guidelines added in 2010 also remained, and schools had to ensure that the lunches met specific nutrition standards.