The Complete Guide To Quick Breads

Baking bread generally causes a chemical reaction. In yeast breads, the reaction is a biological while in quick breads, the reaction is a chemical. It's the quickness of the chemical reaction that make them so popular. Part of their appeal is that they bake faster than breads made with yeast. When it comes to making homemade bread for your breakfast toast, for example, a loaf of banana bread takes far less time to make than a bread recipe that calls for yeast. These quick-baking recipes allow busy home bakers the luxury of having homemade bread for meals without giving up a lot of time. While quick breads have some disadvantages, you can overcome them once you know how to work with them and what to expect from them.

However, it isn't just the speediness that makes them popular. There are lots of quick bread recipes in existence today, so much so that it's unlikely that you'll ever be bored, or even hungry for that matter, when you've decided to embark on a quick bread baking odyssey. These bread recipes can be savory or sweet, shaped like muffins with crumbles on top, filled with plump blueberries, or embrace both spicy and chunky characteristics — like when jalapeños and kernels of corn get added to a boxed cornbread recipe. Here's what you need to know about these quick, delicious and versatile breads.

What is quick bread?

Yeast, or a lack thereof, is the thing that separates quick breads from your standard sandwich breads. To rise, quick bread recipes tap into the chemical reaction caused by the baking powder and baking soda. This reaction creates bubbles in the dough or batter. It's the bubbles that cause the quick bread to rise in the oven. One of the advantages of quick breads is that they don't require kneading like yeast breads do so they go straight into the oven once the batter is done.

On the other hand, in yeast breads, the yeast cells eat the sugar in the recipe, causing the yeast to release ethanol and carbon dioxide gases as a byproduct. The bread dough traps those gases. Because the gases have no place to escape to, the bread rises as the gases attempt to free themselves from the confines of the dough. Yeast breads, unlike most quick breads, must be kneaded to encourage the yeast to activate. They must also be given time to rise between each kneading session. The length of time it takes to make yeast bread is one of its biggest drawbacks for cooks.

However, quick breads also have drawbacks. They can be dense in consistency and crumbly in texture, making them a poor choice as a go-to sandwich bread. Imagine trying to make a sandwich from a zucchini or beer bread recipe, and you understand the inherent challenge of turning a quick bread into a sandwich loaf.

Different types of quick bread

Quick bread batters and doughs come in three basic forms: pour, drop, and dough. Of the three, the dough breads, which are used to make biscuits, scones, and Irish soda bread, are the closest in consistency and texture to yeast breads. Bakers must flatten the dough with a rolling pin and knead it ever so slightly before they can even think about whipping up a batch of biscuits and sausage gravy. Creative baking tools, like biscuit cutters, work with this type of quick bread dough.

On the opposite end of the spectrum lies the pour batter quick breads. Your morning pancakes and waffles, as well as that funnel cake you love, count among the pour batter quick bread recipes you'd likely be familiar with. Finally, beer, banana, and zucchini bread recipes fall in the middle of the spectrum and make up the drop batter quick breads. Drop batters require the help of a spatula to push the batter out of the mixing bowl and into the pan.

It's worth noting that gray areas exist in these classification. More specifically, some baking professionals whittle the list down from three types to two types of quick breads: batter and dough. In these cases, it's helpful to keep in mind that if a quick bread is considered a batter bread, it has eggs in it. Dough breads don't necessarily call for eggs in the recipe.

Why are quick breads quick?

They're quicker to make than yeast breads, though not exactly "quick," the way we understand the word in this age of the wi-fi super-router. The reason baking soda–leavened breads came to be known as quick has everything to do with history. Which brings us to...

A quick history of quick bread

Before the U.S. Civil War, there were beaten biscuits, there were unleavened johnny cakes (a kind of cornmeal flatbread), and there were old-fashioned pound or sponge cakes, leavened by beating egg whites until fluffy and folding them into a batter, gênoise style. There were, of course, good old-fashioned sourdough and yeast bread loaves too.

Breads raised by baking soda — like our beloved banana bread — were unknown. But in 1846, baking soda — sodium bicarbonate—showed up on the scene. New York bakers John Dwight and Austin Church released what would be known, popularly, as saleratus, a thing first refined in France in the 1790s. When incorporated into a batter containing vinegar or soured milk, saleratus would cause a simple chemical reaction that released gas bubbles, yielding breads and cakes with an open, minutely honeycombed texture that registered on the tongue as lightness. The quick bread was born.

The significance of baking powder

A decade later, in 1856, there was a further innovation: baking powder, a mixture of a carbonate or bicarbonate and a weak acid (like tartaric acid, for instance), which meant you didn't need to include an acidic agent in the batter itself.

By itself, baking powder might have been a useful niche product to a nation used to yeasted breads and labor-intensive baking. Then: the Civil War. Within a couple of years, the U.S. was scrambling to fill the gaps in a labor force decimated by war. Suddenly shortcuts, like "quick" breads that would obviate the need for the hand labor, were essential. America developed a liking for baking powder biscuits, for soda breads and scones.

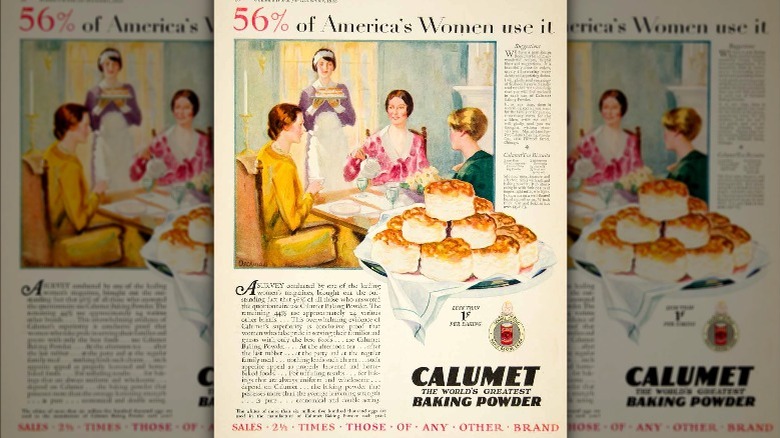

In 1889, the first mega-brand of baking powder was born: Calumet, manufactured in what would come to be known as Calumet City, Illinois, has been leavening cakes, breads, and biscuits ever since.

How does quick bread work?

Just like making pancakes, assembling a quick bread batter calls for two mixtures—from two separate bowls—becoming one. It's so simple, so ingrained in every cook's notion of mixing, it sounds a little ridiculous to break it down, but:

You start by blending the dry ingredients in one bowl—flour, salt, ground spices, and the leavening agent or (if the recipe calls for a mix of baking powder and baking soda) agents. In bowl two, the wets: eggs, liquid fat, milk or other liquid—often acidic ones, like buttermilk or sour cream, to activate the leavening agent. Stir them together, mix in any chunky things, like nuts, dried fruit, or chocolate bits, and bake, in a loaf pan in a moderate oven.

What does baking powder do?

What happens, mostly in the oven, is an act of chemical aeration. A weak acid meets a weak base, and a chemical reaction—the production of carbon dioxide—results. This, of course, produces air pockets in a dough, boosting volume and creating a sensation of lightness and softness on the tongue, while causing that familiar swollen and cracked top. Unlike yeasted breads, which undergo leavening from a number of conditions, all of which have to be working in the correct way, quick breads offer reliable results, time after time.

What is a weak base?

The combo of weak acids and bases is familiar to anyone who's done any baking: baking soda (sodium bicarbonate)—the weak base—allied with cream of tartar, buttermilk or yogurt, or lemon juice, all weak acids. Quick breads that rely solely on baking soda as a base are often called soda breads, like the St. Patrick's Day favorite, Irish Soda Bread. Baking powder, by contrast, contains both an acid and a base—all it needs is a liquid of some kind to start the reaction that produces carbon dioxide, and your quick bread is on the road to rising.

Are all quick breads bread?

Though we think of quick breads as actual breads—loaves of banana or zucchini bread, say—they can be a lot of things. Technically, chemically leavened quick breads come in four types, classified by the consistency of the batter (or dough, for that matter—though we're not considering them here, chemically leavened cookie doughs and pie crusts are definitely in the same category as quick breads).

Ways to bake quick breads

Loaf pan. Cast iron skillet. Muffin tin. These count as just a few of the pieces of equipment you use to bake quick breads. The equipment you choose isn't only a matter of aesthetics, it's a matter of mechanics. For example, baking in either a nonstick or dark pan, regardless of size, allows you to cut down the required baking temperature by 25 degrees Fahrenheit, thanks to the pan's ability to soak up the heat. Those pans can change cooking times, too, for the same reason. And shiny pans give your breads a golden brown crust because they reflect the heat, pulling it away from the bread.

Additionally, adding your favorite cornbread batter to a preheated skillet sizzles the bread's crust until it becomes satisfyingly crispy. However, there are even more advantages to baking quick breads in a skillet. The heavy bottom and side of the skillet ensure that the bread bakes evenly. The baking instructions for the bread often come with recommended pan shape and size — if they do, heed the advice given. For example, if the recipe calls for an 8" x 4" loaf pan, using a 9" x 5" pan leaves you with something closer to pancakes because the batter spreads to fit the pan. Finally, regardless of the pan you choose, it should only get filled about two-thirds of the way full to ensure that the bread dough or batter has room to expand during the baking process.

Different ways to mix quick breads

Baking quick breads is nothing if not a methodical process. They require a separation of the liquid and dry ingredients to get the chemistry to work out just right. As with mathematics, there is an order of operations at play, but that order depends on what you're baking, and which mixing method will help you achieve that product. There are three main mixing methods: The muffin method, the creaming method, and the biscuit method. The type of bread determines the method you use to mix the batter or dough. Your basic buttermilk pancakes, muffins, and loaf breads fall into the muffin method, which sees melted fat, like butter, sugar, eggs, and liquids mixed together before the dry ingredients get poured in. Solid fats mingled with flour and other dry ingredients to make a crumbly dough create scones and biscuits, and unsurprisingly, fall into the biscuit method of quick bread mixing.

In the middle sits the creaming method, which brings together softened fats, like room temperature butter, and sugar, making for a light, fluffy texture. You'll add in the eggs gradually as you stir the fats and the sugar together. The remaining ingredients go in after that. Certain muffin recipes also fall into this category. The texture is the giveaway in this case. A muffin made with the creaming method is more like cake and less like cornbread. Some blueberry muffin recipes, for example, use the creaming method instead of the muffin method.